Virtue as Life’s Competitive Advantage

Employers are starting to realize that what is most valuable about their employees is not their skills but something more fundamental, what are variously being called “distinct elements of talent” and “durable capabilities,” like courage, humility, and perseverance. We know these by another name: virtues. Since most education institutions shy away from discussions about virtue, and character, it is a competitive advantage of Newman Guide schools that we are not afraid to be explicit about our character formation efforts.

I started the project I am going to tell you about, though, not because of employer demand but because I saw a need in our students: a need to understand and practice the virtues better. When we founded the Busch School of Business at The Catholic University of America, we built the entire school around Catholic social doctrine. Every aspect of our curriculum and formation was grounded in authentic Church teaching. But after a few years, it became clear to me that Catholic principles aren’t enough. We have to help students grow in virtue.

Now, I’m not a philosopher or a theologian. I’m a marketing guy. So what I started doing with our students, and now with the wider world, is promoting virtue — selling virtue to the world. Because the world needs it! And here’s how I’m selling it: I ask my audiences, “Is there a way to do more, and yet at the same time make life easier?”

I give an analogy. Our grandson, Owen, was recently learning to walk. He has the muscles. He has the balance. But he does it really slowly, and he’s really focusing on each step. And yet, soon enough, walking becomes habitual for him, and he’s no more thinking about it than you or I do.

There’s a traditional set of habits, not for walking, but for what is arguably just as important: habits for thinking, acting, and feeling — specifically, habits for making decisions, for interacting with others, and for managing our emotions. These are habits that most people unfortunately, these days, never really develop. So we take too long to make decisions, or we make poor decisions. And as a society, we seem to be incapable of fixing the problems we face. We have trouble maintaining relationships with others, or we never create them in the first place Young people not getting married. There are huge divisions in our society. In terms of managing emotions, we have epidemics of anxiety and depression.

What are these habits of thinking, acting, and feeling, that I’m talking about? They are, of course, the virtues. What is a virtue? A virtue is a good habit that makes you good — a habit of human excellence. But virtues are not just about morality. They include both moral excellence and practical excellence more broadly. We Catholics are aware of the moral significance of virtue, but do we understand the practical implications? Both ethics and effectiveness are bound up in every virtue. Courage, for example: is it a moral thing to be courageous, or is it practically useful? It’s both.

Living the virtues is a way to live the Christian life more fully, but also more easily!

Because they’re habits, and when you do something out of habit, that makes it easier. Is it somehow less moral because it’s easier? No! The idea that something must be hard to be moral or virtuous is not a Catholic idea. The more virtuous you are, the easier it is to be good. The more courageous you are, the easier it is to do courageous things.

Can anyone acquire any virtue? Yes, each virtue is a habit. With a little practice, every day, anyone can develop any virtue.

How are virtues different from regular habits like brushing your teeth or making your bed? In three ways:

- Virtues have a wider scope than regular habits. If you build the habit of courage on the football field, you can use it in an interview, at work, in political life, etc. The habit of brushing your teeth is good for, well, brushing your teeth.

- Growing in virtue also makes you happier, as we’ve known since Aristotle, but positive psychology research has since given us extensive empirical evidence for this.

- That same research has demonstrated that growing in each virtue makes you healthier.

Each virtue is a superpower habit, which is why I like to call them superhabits.

How do you grow in a virtue? The same way you grow in any habit, by practicing a little each day. (Read James Clear’s Atomic Habits for some detailed advice.)

The opposite of a virtue is a vice, a bad habit. There are often two opposing vices for each virtue, related to too much and too little concern. For example: courage is the superhabit of dealing with fear, of moving ahead despite being afraid. Too much concern about fear is the vice of cowardice, while too little concern for fear is the vice of recklessness. The right amount of concern for fear is courage: accepting your fears and moving forward.

There are four stages for growing from vice to virtue. Classically they were referred to as vice, incontinence, continence, and virtue. Do you see a problem with the middle two terms? “Incontinence” and “continence,” to the modern ear, are all about bladder control. So instead we use the following terms: unconscious incompetence, conscious incompetence, conscious competence, unconscious competence. The main point is that you’ve not really hit the point of virtue until you reach unconscious competence, where the habit has become so much a part of you that you do it almost without thinking. That’s what it means to be truly virtuous.

Of course, there is also the vitally important role of grace. If growing in virtue is like rowing a boat, the gifts of the Holy Spirit, including wisdom, understanding, counsel, fortitude, knowledge, piety, and fear of God, are like sails, allowing us to receive grace — the wind — which enables us to exercise each virtue more easily, effectively, and supernaturally.

Finally, how many virtues are there? Can any positive, abstract noun be a virtue? Is harmony a virtue? Prosperity? Serenity? Unity? Integrity? No, not in the classical sense of a good habit.

Is there anything that can tell us how many virtues there are and which of them we should focus on? What we need is not just a list of virtues, but a system which shows how they all work together and what the complete list is. Here’s where we turn to St. Thomas Aquinas. In his treatise on the virtues in the Summa Theologiae, he shows how there is a specific virtue for every part of life.

How does he do this? He starts by distinguishing between supernatural and natural life and observing that there are virtues for the supernatural life: faith, hope, and charity (or love). He then differentiates our natural lives into intellectual and practical life. The intellectual life has its own proper virtues: wisdom, science, and understanding.

Aquinas then differentiates the practical life into thoughts, actions, and feelings — intellect, will, and passions. For each of these dimensions in life, there’s a specific cardinal virtue. For thinking, which in practical terms usually means making decisions, we have the cardinal virtue of prudence or practical wisdom — the superhabit of making wise decisions.

For actions, which usually mean interactions with others, there’s the virtue of justice — the superhabit of being fair to others and respecting their dignity. We then can divide feelings into two kinds: those that attract, and those that repel — desires and fears. For our fears, we have the virtue of fortitude — the superhabit of moving forward, even though you might be afraid. And for our desires, we have temperance or self-discipline — the superhabit of only giving in to our desires when it makes sense to do so.

If you’ve ever wondered why we have these four cardinal virtues — prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance, now you know — it’s because just these four virtues cover every aspect of our practical, daily lives: our thoughts, actions, and feelings. Just imagine if your children — or you — had these four habits, fully. How much more effective at life would you be, and how much easier would your life be? And how much happier would you be? You’d make good, wise decisions, almost effortlessly. You’d treat everyone around you fairly and reasonably. You’d be in charge of your desires, only following them when it made sense to do so, and you’d be able to face the difficult challenges that life throws at you, without giving in.

Together, these four cardinal virtues, along with several virtues allied to them make up what might be called the human operating system. Think about what happens when you don’t update the operating system on your phone or laptop. Your apps start to slow down, or they don’t work at all. The same thing is happening in our society — our ability to get things done, to relate to others, to manage our emotions is breaking down. We all need an update to our human operating system by growing in virtue.

While this can be exciting, it is also somewhat overwhelming to our students. Growing in self-discipline, justice, or courage is not an easy thing. Where do I even begin? Here’s where Aquinas’s genius kicks in. He recognizes that each of the cardinal virtues has several associated or “allied” smaller virtues, which are more accessible. You can start growing in any of them by practicing small, simple, daily steps.

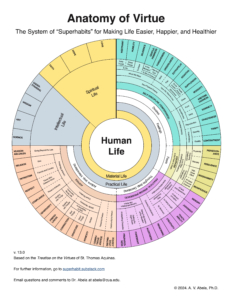

I’ve captured this in the following diagram:

You start in the center, and each ring stands for a distinction: between spiritual and material life; between intellectual and practical; between thoughts, actions, and feelings; between fears and desires; and so on. And on the outer ring, you have all the allied virtues: 15 for self-discipline, four for courage, and so on.

If you want to learn more about upgrading the “human operating system” by cultivating virtue, especially, in our young people, connect with me through these sources:

superhabit.substack.com

www.forbes.com/sites/andrewabela

Superhabits: The Universal System for a Successful Life is available for preorder from Sophia Press https://sophiainstitute,com/product/super-habits/

Dr. Andrew Abela, Dean of the Busch School of Business at The Catholic University of America, delivered this address at The Cardinal Newman Society’s 2024 Newman Guide College Leaders Summit. The text has been reduced and edited for publication.