Eucharist, The Heart of Catholic Education

“The sacred liturgy does not exhaust the entire activity of the Church…. Nevertheless, the liturgy is the summit toward which the activity of the Church is directed; at the same time, it is the font from which all her power flows” (The Second Vatican Council’s Dogmatic Constitution on the Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium, 9-10).

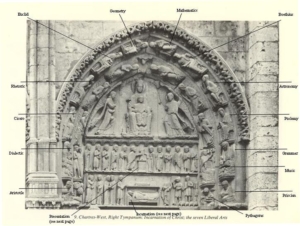

We begin with an image. One of the most profound visual statements of the Catholic educational ideal — namely, the integration of the various disciplines of human wisdom in the light of the divine Wisdom incarnate — is portrayed in the tympanum over the right door to the main entrance of the Cathedral of Our Lady in the city of Chartres, France.

Chartres was the sight of a tremendous intellectual renaissance in the twelfth century, which witnessed not only the construction of this magnificent cathedral, but also the founding of a remarkable academic institution, the Cathedral school. This was an institution that brought together in one place for the purposes of research and teaching many of the best and wisest scholars of the day, an institution that would serve as a model for the creation and development of that amazing medieval invention, the university.

For the great scholars and visionaries at Chartres, their challenge was to create an educational framework in which the disciplines of human wisdom might be married to the revelation of divine Wisdom in the person of Jesus Christ. Indeed, this portal sculpture is an artistic expression of precisely that intellectual vision.

If you do an online search for an image of “the seven liberal arts and the western portal at Chartres,” you will find several good photographs of the tympanum, some of which have the characters labeled. In the middle, you will see the famous Sedes Sapientae, or holy “Seat of Wisdom.” Surrounding it in the archivolts are personifications of the seven liberal arts: on the bottom right, grammar, who is teaching two boys to write; moving then to the bottom left, we find dialectic, in whose right hand is a flower and in whose left hand is the head of a barking dog; proceeding around clockwise, we find rhetoric, who is pictured proclaiming a speech; geometry, who is shown writing figures on a tablet; arithmetic, whose attributes have been effaced over the centuries, so no one is sure what she is doing; astronomy, who is gazing up at the sky; and finally, moving to the inner archivolt, music, who is playing two instruments: the twelve-stringed harp and some bells. Underneath each of the arts is a representation of the thinker classically associated with that discipline: Priscian for grammar, Aristotle for dialectic, Cicero for rhetoric, Euclid for geometry, Boethius for arithmetic, Ptolemy for astronomy, and most likely Pythagoras for music, about whom Cassiodorus had related the story that he had “invented the principles of this discipline from the sound of bells and the percussive extension of chords.”

Here at Chartres, we see in concrete, visible form the artistic record of an attempt to integrate human wisdom, as exemplified by its instruments — namely, the seven liberal arts — with Wisdom incarnate in the person of Jesus Christ. The visual movement of the image, moreover, goes in both directions. The arts and disciplines of human wisdom are seen as a preparation for an increased understanding of faith: they surround and support the image of Wisdom Incarnate in the center. By the same token, the Seat of Wisdom is pictured at the center as both the source and summit of all human wisdom. Mary sits at the center of the arts as a paradigm — as the “Seat of Wisdom” — because she is a model of one who obediently responded to God’s word, thus giving birth (in her case, quite literally) to God’s Wisdom Incarnate.

This point is emphasized in the two friezes below, both of which illustrate the events of the Christ’s birth. In the bottom frieze (reading from left to right), we see the Annunciation, the Visitation, and in the middle, the birth of Christ, with the angel leading the shepherds in from the right, sheep in tow. In the top frieze, we see Mary and Joseph presenting Jesus at the altar in the Temple. If you look closely, you’ll see that, unfortunately, likely due to violence done to the cathedral during the French Revolution, Christ is missing His head.

I am sometimes asked: “Doesn’t Jesus look sort of a like a loaf of bread?” The answer is, yes, and it’s not just because He’s missing his head. Scholars tell us that these images were carved in response to a Eucharistic controversy raging at the time, in which certain groups were emphasizing the presence of the Risen Christ of heaven in the Eucharist, perhaps to the detriment of an understanding of the Eucharist which might include the living Christ who lived and walked the earth. Here at Chartres, we see an attempt to correct that potential misunderstanding by including within the Eucharistic imagery scenes from Christ’s birth. This theological and historical context helps explain why the artist pictures the child Jesus on top of an altar rather than in Mary’s arms or in a manger.

Let me stress that such details are not merely artistic trivia. Lying behind this entire set of images is a very conscious theology of Incarnation and sacramentality. If God has created the world and reveals Himself to us through His creation, then we have the possibility (as St. Paul tells us) of coming to know the invisible attributes of God through the visible things of creation. As in the visible, earthly elements of the Eucharist, we are meant to see the real presence of Christ, the Word made flesh, so also, in the visible, earthly elements of creation, we are meant to see the presence of God’s creative Word and Wisdom.

It would be a similar theology of Incarnation, moreover, that would allow the word and wisdom of God to become incarnate in actual, human language and thus, by extension, present and embodied on a written page such as the Scriptures.

Thus, as the scholars at Chartres understood, we must learn to read both the Book of Nature and the Book of Scripture, for they are not mutually exclusive. Rather, on this view, they will ultimately illumine each other because they both have the one God as their Author. Indeed, on the classical Christian understanding of the seven liberal arts, the trivium (or “threefold way”), which includes grammar, rhetoric, and logic, are precisely the disciplines that teach us how to read and understand the Book of Scripture; while the quadrivium (the “fourfold way”), the arts of geometry, mathematics, astronomy, and music, are those that guide us in our understanding of the Book of Nature. The portal image makes clear, however that this reading — whether of one book or the other (and notice that each of the classical thinkers associated with the arts is pictured writing in a book, which is the classic medieval pose for the four Gospel writers: Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John) —must always be done in the light of the divine Wisdom incarnate.

Note how, in this vision of an authentically Catholic education, all the disciplines are present and effectively integrated. This aspiration to unity and integration of all the disciplines is one that has continued to inspire the best Catholic educational institutions in the centuries since. It was the vision that inspired the nineteenth century theologian and saint, John Henry Cardinal Newman, to write his important and influential book, The Idea of a University, although it was a vision he had nurtured for years. In one of his earlier sermons, for example, he wrote:

Here, then, I conceive, is the object of … setting up universities; it is to reunite things which were in the beginning joined together by God and have been put asunder by man…. It will not satisfy me, what satisfies too many, to have two independent systems, intellectual and religious, going at once side by side, by a sort of division of labor, and only accidentally brought together. It will not satisfy me, if religion is here and science there, and young men converse with science all day and lodge with religion in the evening…. I wish the intellect to range with the utmost freedom, and religion to enjoy an equal freedom, but what I am stipulating is, that they should be found in one and the same place and exemplified in the same persons (Cardinal Newman, in Sermon I of Sermons on Various Occasions).

What is especially poignant in this passage is the marriage imagery: the notion that in setting up universities, our goal should be “to reunite things which were in the beginning joined together by God and have been put asunder by man.” The rule in contemporary universities, however, is to allow our students to fall into (indeed, we often insist that they fall into) one or another of the disciplines, to the detriment of — perhaps even the exclusion of — the others. It is perhaps not inaccurate to say of the faculty and staff of the modern university that they are like the orphaned children of a sad divorce: a divorce not only between human wisdom and divine Wisdom, but also between and within the disciplines themselves. The job of a Christian university, then, is to do what secular culture cannot: unite what has been put asunder by man.

Bridging these divides, uniting what has been put asunder, and integrating what should be seen as a whole, was the challenge set forth by Pope John Paul II in his encyclical Ex corde Ecclesiae. Allow me, if I may, to quote the passage I have in mind in full.

The integration of knowledge is a process, one which will always remain incomplete; moreover, the explosion of knowledge in recent decades, together with the rigid compartmentalization of knowledge within individual academic disciplines, makes the task increasingly difficult. But a University, and especially a Catholic University, “has to be a ‘living union’ of individual organisms dedicated to the search for truth … It is necessary to work towards a higher synthesis of knowledge, in which alone lies the possibility of satisfying that thirst for truth which is profoundly inscribed on the heart of the human person.” Aided by the specific contributions of philosophy and theology, university scholars will be engaged in a constant effort to determine the relative place and meaning of each of the various disciplines within the context of a vision of the human person and the world that is enlightened by the Gospel, and therefore, by a faith in Christ, the Logos, as the center of creation and of human history (Ex corde Ecclesiae 35).

Bridging these divides — bridging especially the significant division between what author C. P. Snow once called “the two cultures”: the natural sciences, on the one hand, and the humanities, on the other — is necessary not only for the health of the secular academy, but it is an absolute requirement, as Newman and Pope John Paul II have made clear, for a truly Catholic education. Only if we help our students bridge this divide will we have helped them achieve the kind of unified and integrated human wisdom — both of themselves and of the world — that could serve as the proper handmaiden of the Divine Wisdom Incarnate.

Randall Smith is a Professor of Theology at the University of St. Thomas, Houston. He is the author of four books, including How to Read a Sermon by Thomas Aquinas: A Beginner’s Guide (Emmaus); Aquinas, Bonaventure, and the Scholastic Culture of Medieval Paris (Cambridge); and From Here to Eternity: Reflections on Death, Immortality, and the Resurrection of the Body (Emmaus). His next book — the only book-length commentary in English on Bonaventure’s Journey of the Mind into God — will be available from Cambridge University Press in the fall of 2024.