Pride on Full Display in ‘Hesburgh’ Documentary

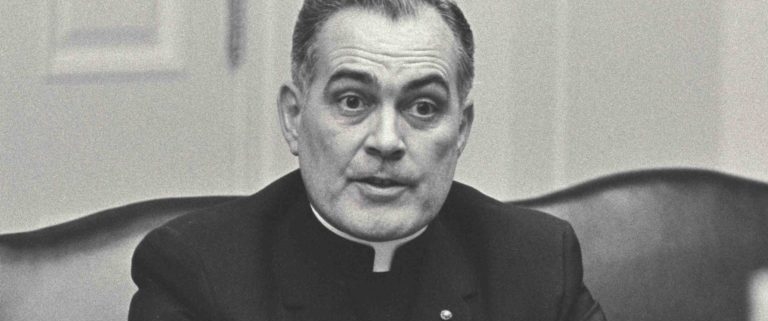

The mere fact that the laudatory, even triumphal, documentary Hesburgh will enjoy a limited release in theaters beginning today would no doubt have been deeply satisfying to the late Holy Cross Father Theodore Hesburgh, who led the University of Notre Dame (1952-1987) to enormous growth and prestige.

From beginning to end, the film makes the obvious point that Father Hesburgh was important and accomplished much on a human scale. Notre Dame’s enrollment, public reputation, academic standing, physical campus and donor support all improved considerably under his leadership.

He was also an influential leader on some of the most important issues of his time, especially civil rights for African Americans. The film’s images include a myriad of leaders — popes, U.S. presidents, celebrities and others — with whom Father Hesburgh associated, collaborated and sometimes clashed.

But the documentary largely glosses over important questions about Father Hesburgh’s thinking and impact and his conflicts with Church leaders, doctrine and the mission of Catholic education. It simply reports — without any real analysis and in a decidedly favorable way — his leadership in crafting the Land O’ Lakes Statement that declared the independence of Catholic colleges from the bishops and magisterium of the Church, his legal separation of the university from the Holy Cross order (thus increasing his own independence from religious superiors), his embrace of a radicalized “academic freedom” in the manner of modern research universities, and his delight in Notre Dame’s 2009 commencement honors for pro-abortion President Barack Obama.

Even while the film champions Father Hesburgh’s determination to engage with all viewpoints, the filmmakers shy away from any serious examination of charges that he had in some ways betrayed the Church and the mission of Catholic education. It’s not even acknowledged that 83 Catholic bishops publicly opposed the Obama honors.

The film also fails to address the morally serious concern that Father Hesburgh, through his work with the Rockefeller Foundation, and together with his Notre Dame colleagues, quietly advanced a population control and family planning agenda. Or that he relied on Father Richard McBrien to reform the Notre Dame theology department as a center of liberal theology. Or that, when Cardinal John O’Connor of New York publicly scolded New York politicians, Gov. Mario Cuomo and congresswoman Geraldine Ferraro, both Catholics, for their public advocacy of abortion rights, Father Hesburgh welcomed the New York governor to Notre Dame for a landmark speech that claimed a “latitude in judgment” within Catholic teaching that permits a Catholic to privately hold that abortion is unjust killing while publicly championing laws that keep it legal, out of respect for others who disagree with our beliefs. These facts, highly relevant to Father Hesburgh’s pursuit of a “great Catholic university,” are simply ignored in more than two hours of film.

Rather, the documentary features multiple tributes from mostly “progressive Catholics” who include former students and colleagues at Notre Dame, writers from the National Catholic Reporter, and even House Speaker Nancy Pelosi. It all has the feel and the gloss of an episode of Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous. Viewers are invited to indulge in awe and envy.

‘A Great Catholic University’

A deeper and more honest assessment would have acknowledged that Father Hesburgh’s legacy is complicated and has in fact done significant damage to the university that he strove to build and to the Church in the United States to which he gave his life in service.

Father Hesburgh was driven to transform Notre Dame into a “great Catholic university” built on human “excellence,” as the film mentions briefly. But how that pursuit evolved over his 35 years at the helm of Notre Dame — and influenced subsequent University leaders — is far better explained in the new biography, American Priest: The Ambitious Life and Conflicted Legacy of Notre Dame’s Father Ted Hesburgh (Image, 2019) by Holy Cross Father Wilson Miscamble. Father Miscamble has taught at Notre Dame for more than 30 years and is a vocal advocate for restoring what he and many perceive as Notre Dame’s lost Catholic identity, and so he searches for clues to why that identity slipped under Father Hesburgh’s leadership. But as a serious historian, he also is careful to report facts objectively and thoroughly.

For instance, Father Miscamble provides the surprising revelation that during Father Hesburgh’s first term in the 1950s, he publicly embraced a vision of Catholic higher education that resembled Blessed John Henry Newman’s Idea of a University. Nevertheless, Father Hesburgh’s actual emphasis in building up Notre Dame was on raising funds, building Notre Dame’s reputation through association with prominent academic and public figures, and transforming the university in the image of the secular research institution.

According to Father Miscamble, Father Hesburgh gave very little attention to ensuring an integrated Catholic curriculum and a faithfully Catholic faculty — resulting in a dramatic slide toward secular education that continues today.

Father Miscamble’s biography portrays a priest who had incredible natural leadership abilities but failed to rely on God’s grace and the Church’s timeless wisdom. It would have been a truly remarkable witness for Father Hesburgh to have brought Notre Dame to greater acclaim while also amplifying the university’s Catholic identity. After all, if the Catholic faith really is transcendental — true, beautiful and good — then doesn’t it have the power to attract?

Instead, Father Hesburgh’s career as president appears to have been an exercise of misplaced pride in human achievement, especially his own capabilities, and greater faith in state and secular institutions than the goodness of the Church.

Father Hesburgh was a prayerful priest who celebrated Mass daily and had a devotion to Mary, yet in his presidency he had this air of “going it alone” and failing to appreciate Catholic education as fundamentally an encounter with Christ.

In Hesburgh, he states plainly, “There had to be a way to balance faith and academics” — as if the two are in conflict. Again, he asks: “Was it possible to be both a great university and Catholic? I believed it was as long as there was balance.”

Because of his failure to acknowledge the Catholic faith as truth that is fundamental, not opposed, to the academic enterprise, Father Hesburgh’s impressive human achievements have today resulted in the sort of unintended confusion and lack of structural integrity that befell the builders at Babel.

Perhaps without intending to, director Patrick Creadon highlights Father Hesburgh’s unsettling certainty of the wisdom of his actions and opinions — even those in opposition to the Church — by including a voice-over by actor Maurice LaMarche, who pretends to be Father Hesburgh recounting his own tale using actual quotes from Hesburgh’s writings and recordings. The device is awkward for a film that is something of a congratulatory eulogy for the priest, who died in 2015. Right or wrong, LaMarche’s tone makes Father Hesburgh seem rather smug.

I am rather sure the makers of Hesburgh would not agree with Father Miscamble’s assessment of Father Hesburgh’s legacy, but at least an assessment is made in American Priest. In the documentary, there is no movement beyond the Hesburgh “hagiography” (a term suggested by Father Miscamble) that seems to prevail within the Notre Dame community.

Clearly Father Theodore Hesburgh had enormous influence across the Church and U.S. society. His choices had real consequences for Notre Dame and Catholic education nationwide.

While Hesburgh presents an intriguing look at the many important activities of an important man, his legacy is left to more serious biographers like Father Miscamble to straighten out.

This article was first published at The National Catholic Register.

Photo by David Mark via Pixabay CC0

Photo by David Mark via Pixabay CC0