Policy Standards on Secular Academic Materials and Programs in Catholic Education

Catholic education fulfills a divine mission, to provide for the common good of humanity and the Supreme Good of those being educated.[1] To accomplish this mission, Catholic schools and colleges create authentic, faith-based communities which educate students’ intellectual, moral, emotional, physical, and spiritual gifts within a rich Catholic worldview.[2]

Faithful Catholic education draws upon the best available programs and materials to aid in instruction that fulfills its Catholic mission. Books and programs which are specifically designed to foster a Catholic worldview are a natural choice for Catholic education, but sometimes secular materials and programs—which may include textbooks, lessons, and activities—can also fulfill the requirements of providing content to an already enriched Catholic curricular (e.g., math and science textbook series) and extracurricular foundation.

Such materials and programs must be carefully evaluated to determine if their underlying philosophy, content, and activities are aligned to the mission of Catholic education and, if used, what adaptations might be needed.

The success of Catholic education is not dependent on doing a better job of teaching secular texts or programs or getting higher test scores on standardized tests than public institutions. Catholic educators teach and do more. This means they must ask more of any material or program imported into the educational environment and be ready to heavily adapt it toward a greater end. Catholic educators must also be quick to realize that some resources will be woefully insufficient, and others may have elements that actually work against the Catholic mission.

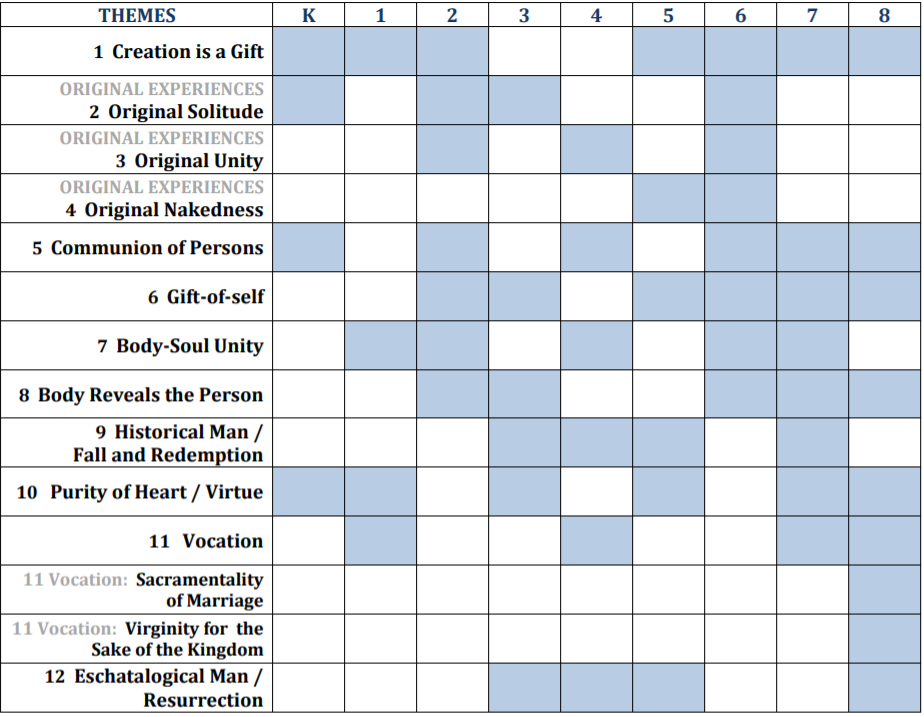

This guide presents principles, standards, and resources to assist Catholic educators in the evaluation of prospective secular materials and programs. The Cardinal Newman Society also has a series of analyses applying these principles and standards to particular secular resources frequently found in Catholic education, including Advanced Placement (AP) courses, International Baccalaureate (IB) programs, and secular character development programs. The Cardinal Newman Society’s Catholic Curriculum Standards[3] and Standards for Christian Anthropology (with Ruah Woods Press)[4] are also available to provide guidance in ensuring that critical elements central to Catholic elementary and secondary education are being delivered throughout the academic program.

Principles

Principle 1: A fundamental element of Catholic education is the evangelization, catechesis, and sanctification of the student.

Catholic education is an expression of the Church’s mission of salvation and an instrument of evangelization:[5] to make disciples of Christ and teach them to observe all that He has commanded,[6] preparing students to fulfill God’s calling in this world so as to attain the eternal kingdom for which they were created.[7]

Principle 2: A fundamental element of Catholic education is that it forms Christian communion and identity.

As a faith community in unity with the Church and in fidelity to the Magisterium, students, parents, and educators give witness to Christ’s loving communion in the Holy Trinity.[8] The Catholic school or college is a place of ecclesial experience, in which the members model confident and joyful public witness in both word and action and teach students to live the Catholic faith in their daily lives.[9] The community itself is a means of education and formation[10] and is nurtured by the consistent and public witness of employees and volunteers who abide by Church teachings and the moral demands of the Gospel.[11]

Principle 3: A fundamental element of Catholic education is the integral formation of the human person: body, mind, and spirit.

Catholic education promotes the integral formation of the human person by developing each student’s physical, moral, intellectual, and spiritual gifts in harmony, teaching responsibility and right use of freedom.[12]

The religious, aesthetic, and creative senses are developed along with formation of the will and dispositions.[13] Catholic education is rooted in a Christian understanding of the dignity of the human person who, created in the image and likeness of God,[14] is at once corporal and spiritual,[15] made in perfect equality and complementarity as male and female,[16] with a fallen nature redeemed by Christ’s death on the cross.[17]

Principle 4: A fundamental element of Catholic education is that it imparts a Christian understanding of the world.

Catholic education seeks to integrate faith with reason and synthesize faith with life and culture. In the light of faith, Catholic education critically and systematically transmits the secular and religious “cultural patrimony handed down from previous generations,” especially that which makes a person more human.[18] Both educator and student are called to participate in the dialogue of culture and to pursue “the integration of culture with faith and of faith with living.”[19]

Catholic education imparts “a Christian vision of the world, of life, of culture, and of history,” ordering “the whole of human culture to the news of salvation.”[20] A hallmark of Catholic education is to “bring human wisdom into an encounter with divine wisdom”[21] and prepare students for the evangelization of culture and for the common good of society.[22]

Standards for Policies Related to Secular Materials and Programs

In Catholic education, policies involving the use of secular materials and programs (including textbooks, lessons, and activities):

- support and protect Catholic schools and colleges as educational communities of evangelization that promote the salvation of students and service to the common good;

- ensure that the school or college environment, staff, and leadership remain fully committed to faithful Catholic education;

- place priority on the selection of Catholic materials and programs over secular options, whenever possible, and with due consideration of the mission and objectives of Catholic education;

- ensure fidelity to the magisterium of the Catholic Church in all lessons, activities, and programs;

- ensure that secular materials or programs do not cause scandal, conflict with Catholic teaching, or cause confusion about the truth of Catholic teaching, including promotion of atheism, agnosticism, relativism, materialism, or false ideology about the human person;

- ensure that secular materials and programs help students develop their intellectual, moral, emotional, physical, and spiritual talents harmoniously without contradiction to Catholic teaching and Christian anthropology;

- ensure that secular materials and programs do not impede students’ development of a Catholic understanding of the world and the human person or obstruct the goal of uniting faith and reason and synthesizing faith with life and culture;

- ensure that secular materials and programs are adapted or richly augmented as necessary with resources and opportunities to integrate Catholic teaching and practice and transmit a Catholic understanding of the human person and the world; and

- prevent formal cooperation or illicit material cooperation with evil by the use of secular materials and programs, including any collaboration with a secular organization or publisher that causes scandal or confusion about the Catholic faith or causes doubt regarding the school or college’s faithful commitment to the mission of Catholic education.

Operationalizing the Standards

To meet these core standards, policies and practices such as those below can be of assistance:

- The school or college uses curriculum standards, such as the Newman Society’s Catholic Curriculum Standards and Standards for Christian Anthropology (with Ruah Woods Press) for grades K-12, to specifically target and address the integration of faith and reason and the synthesis of faith and life and culture.

- The curriculum is designed to facilitate an understanding of objective reality, including transcendent truth, which is knowable by reason and revelation. It specifically counters any secular programs that may seem to promote atheism, agnosticism, relativism, materialism, or false ideology about the human person.

- The school or college ensures that secular materials and programs do not place excessive demands in testing, teacher formation, or curriculum that crowd out the priorities of Catholic education and a strong Catholic culture.

- Secular history programs and texts which espouse political or social activism should be avoided, but if used, they are supplemented to ensure that the principles of Catholic social teaching are taught, compared, and understood.

- Secular science materials and programs are carefully examined for any philosophies, positions, and statements, either explicit or implicit, that may run counter to Church teaching. Such materials and programs should be avoided, but if used, they are countermanded with clear Church teaching and thorough explanation to ensure that students understand the differing philosophies and appreciate the harmony of faith and reason and God and nature.

- Secular human sexuality programs—and those elements of human sexuality addressed in science, psychology, literature, and history—should always further discussion and Christian understanding of the human person, should be integrated with Catholic religious and moral instruction, and taught in collaboration with parents at the K-12 level.

- Programs promoting global citizenry should not be allowed to mask the more profound reality and Catholic emphasis on the transcendent and universal destination of humanity in God. The principle of subsidiarity should be emphasized to counter a false globalism. The assumption that human ills are solvable by human programs and human self-mastery alone, rather than reliance on God’s grace, mercy, and salvation, are held in check.

- Courses in philosophy accompany but do not replace catechesis and theology courses.

- Instruction in virtue and morality must not pre-emptively surrender or silence religious insight and revelation, by attempting to ground morality and dignity on entirely secular grounds.

Catholic educators should unleash the entirety and integrity of human wisdom, including and especially the Church’s inspired wisdom, in their efforts to equip students to attain and practice heroic virtue in the post-modern world.

Possible Questions

For questions about particular materials and programs—including Advanced Placement courses, the International Baccalaureate program, the Meeting Point sexual education program, and secular character development programs—The Cardinal Newman Society publishes separate reviews with detailed recommendations. See the Newman Society website for these reviews.

Question: The best and most up-to-date materials and the programs with the most resources and supports—especially in science, math, grammar, and social studies—are all secular. They are the only reasonable choices for most Catholic schools and colleges. So why even bother worrying about any of this? There is no “Catholic” math, grammar, or science.

Response: Like secular education, Catholic education studies reality using the appropriate methods for the subject at hand and delves deeply into each specific academic discipline on its own terms. So, yes, Catholic educators can use secular materials in these and other areas. But Catholic education is also specifically and distinctly open to the uncovering of transcendent truths which surpass and integrate the disciplines.

For example, Catholic educators can use secular science materials but will also want to, at some place in the curriculum, ensure that students can confidently explain and promote the relationship and unity of faith and reason. They should know the reality that the God of nature and the God of the Catholic faith are one and the same God. They should develop the ability to evaluate the errors present in the belief system of scientific naturalism, which incorrectly claims that scientific exploration and explanation are the only valid sources of knowledge.

In another example, the study of math can also be better pursued by highlighting its transcendent dimension as a reflection of the good, true, and beautiful. Students should develop the ability to reveal qualities of being and the presence of God in mathematical order. Catholic educators also want their students to evaluate the ongoing nature of mathematical inquiry, its inexhaustibility, and its opening to the infinite. Students should develop a sense of wonder about mathematical relationships and confidence in mathematical certitude, and they should understand the unique nature of that certitude, which is not directly transferable to other areas of inquiry into the truth of things.

There is much more that Catholic educators are doing and exploring in most academic disciplines, so while they can and sometimes must use secular materials and programs, they must not limit inquiry or teaching to secular perspectives alone.

Question: Parents demand and colleges respect secular programs such as the Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate (IB) programs and tests. If a Catholic school does not compete with other schools and provide such opportunities to students, it may suffer in its reputation and enrollment. Shouldn’t Catholic schools go all in and work on the terms of the secular programs, for the good of the school and the students?

Response: Without dismissing the prestige of such tests and their impact on college admissions, it is critical for Catholic schools to remember that their core purpose is not to deliver access to college and credit. Their purpose is the dissemination and discovery of truth, the salvation of students, and service to humanity. Testing need not get in the way of these ends, but if not carefully managed, it can. Catholic schools must protect against this to ensure that authentic learning and the dissemination of a Catholic worldview is not negatively impacted.

Catholic education is expansive and holistic. It teaches things which cannot be easily measured, tested, or translated to academic credit. So, while Catholic schools can offer high-stakes testing and credit, they must ensure that these do not hinder the flexibility, freedom, discovery, and awareness that enkindles a love for truth wherever it might be found.

Question: Why can’t a Catholic school use a secular program focused on virtue, character development, or sexual ethics that is based on the natural law and does not emphasize religion? The ability to construct a universal set of human values based on reason and nature may even make it more palatable and attractive to modern students.

Response: While such programs can be used when necessary, they must be supplemented with biblical and magisterial guidance. Reason and humanity alone are not sufficient, since we also have a religious nature which cannot be denied without peril. The humanism of the best ancient Greeks and Romans, the civic virtues of Confucianism, or the science of human reproduction are not enough to build a complete human character or consistent moral framework consonant with the way and the end for which we were created.

Humanity cannot be saved and find happiness based on programs and ideas of its own making. There is no simple human-based fix or program or series of insights to the problem of original sin and humanity’s weakness. Christ alone fully reveals man to himself and unlocks the keys to virtue and happiness. He cannot be left out of human formation without consequence in any school, let alone a Catholic school, whose very function is to lead students to their destiny and salvation in Him.

This document was developed with substantial comment and contributions from education, legal, and other experts. Lead authors are Denise Donohue, Ed.D., Director of the Catholic Education Honor Roll at The Cardinal Newman Society, and Dan Guernsey, Ed.D., Senior Fellow at The Cardinal Newman Society and principal of a diocesan K-12 Catholic school.

Appendix A: Selections from Church Documents Informing this Topic

…the Catholic school tries to create within its walls a climate in which the pupil’s faith will gradually mature and enable him to assume the responsibility placed on him by Baptism. It will give pride of place in the education it provides through Christian Doctrine to the gradual formation of conscience in fundamental, permanent virtues—above all the theological virtues, and charity in particular, which is, so to speak, the life-giving spirit which transforms a man of virtue into a man of Christ. Christ, therefore, is the teaching-centre, the Model on Whom the Christian shapes his life. In Him the Catholic school differs from all others which limit themselves to forming men. Its task is to form Christian men, and, by its teaching and witness, show non-Christians something of the mystery of Christ Who surpasses all human understanding.

Congregation for Catholic Education, The Catholic School (1977) 47

Since true education must strive for complete formation of the human person that looks to his or her final end as well as to the common good of societies, children and youth are to be nurtured in such a way that they are able to develop their physical, moral, and intellectual talents harmoniously, acquire a more perfect sense of responsibility and right use of freedom, and are formed to participate actively in social life.

Holy See, Code of Canon Law (Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1983) 795

Students should be helped to see the human person as a living creature having both a physical and a spiritual nature; each of us has an immortal soul, and we are in need of redemption. The older students can gradually come to a more mature understanding of all that is implied in the concept of “person”: intelligence and will, freedom and feelings, the capacity to be an active and creative agent; a being endowed with both rights and duties, capable of interpersonal relationships, called to a specific mission in the world.

Congregation for Catholic Education, The Religious Dimension of Education in a Catholic School (1988) 55

The human person is present in all the truths of faith: created in “the image and likeness” of God; elevated by God to the dignity of a child of God; unfaithful to God in original sin, but redeemed by Christ; a temple of the Holy Spirit; a member of the Church; destined to eternal life.

Congregation for Catholic Education, The Religious Dimension of Education in a Catholic School (1988) 84

Not a few young people, unable to find any meaning in life or trying to find an escape from loneliness, turn to alcohol, drugs, the erotic, the exotic etc. Christian education is faced with the huge challenge of helping these young people discover something of value in their lives…We must cultivate intelligence and the other spiritual gifts, especially through scholastic work. We must learn to care for our body and its health, and this includes physical activity and sports. And we must be careful of our sexual integrity through the virtue of chastity, because sexual energies are also a gift of God, contributing to the perfection of the person and having a providential function for the life of society and of the Church. Thus, gradually, the teacher will guide students to the idea, and then to the realization, of a process of total formation.

Congregation for Catholic Education, The Religious Dimension of Education in a Catholic School (1988) 13, 84

A school uses its own specific means for the integral formation of the human person: the communication of culture… if the communication of culture is to be a genuine educational activity, it must not only be organic, but also critical and evaluative, historical and dynamic. Faith will provide Catholic educators with some essential principles for critique and evaluation; faith will help them to see all of human history as a history of salvation which culminates in the fullness of the Kingdom. This puts culture into a creative context, constantly being perfected.

Congregation for Catholic Education, Lay Catholics in Schools: Witnesses to Faith (1982) 20

Catholic schools provide young people with sound Church teaching through a broad-based curriculum, where faith and culture are intertwined in all areas of a school’s life. By equipping our young people with a sound education, rooted in the Gospel message, the Person of Jesus Christ, and rich in the cherished traditions and liturgical practices of our faith, we ensure that they have the foundation to live morally and uprightly in our complex modern world. This unique Catholic identity makes our Catholic elementary and secondary schools “schools for the human person” and allows them to fill a critical role in the future life of our Church, our country, and our world.

U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, Renewing Our Commitment to Catholic Elementary & Secondary Schools in the Third Millennium (2005)

From the nature of the Catholic school also stems one of the most significant elements of its educational project: the synthesis between culture and faith. The endeavor to interweave reason and faith, which has become the heart of individual subjects, makes for unity, articulation, and coordination, bringing forth within what is learned in a school a Christian vision of the world, of life, of culture, and of history.

Congregation for Catholic Education, The Catholic School on the Threshold of the Third Millennium (1997) 14

Literature and the arts are also, in their own way, of great importance to the life of the Church. They strive to make known the proper nature of man, his problems and his experiences in trying to know and perfect both himself and the world. They have much to do with revealing man’s place in history and in the world; with illustrating the miseries and joys, the needs and strengths of man and with foreshadowing a better life for him. Thus they are able to elevate human life, expressed in multifold forms according to various times and regions.

Saint Paul VI, Gaudium et Spes (1965) 62

Teachers should guide the students’ work in such a way that they will be able to discover a religious dimension in the world of human history. As a preliminary, they should be encouraged to develop a taste for historical truth, and therefore to realize the need to look critically at texts and curricula which, at times, are imposed by a government or distorted by the ideology of the author… they will see the development of civilizations, and learn about progress…When they are ready to appreciate it, students can be invited to reflect on the fact that this human struggle takes place within the divine history [of] universal salvation. At this moment, the religious dimension of history begins to shine forth in all its luminous grandeur.

Congregation for Catholic Education, The Religious Dimension of Education in a Catholic School (1988) 58-59

Every society has its own heritage of accumulated wisdom. Many people find inspiration in these philosophical and religious concepts which have endured for millennia. The systematic genius of classical Greek and European thought has, over the centuries, generated countless different doctrinal systems, but it has also given us a set of truths which we can recognize as a part of our permanent philosophical heritage.

Congregation for Catholic Education, The Religious Dimension of Education in a Catholic School (1988) 57

The curriculum must help the students reflect on the great problems of our time, including those where one sees more clearly the difficult situation of a large part of humanity’s living conditions. These would include the unequal distribution of resources, poverty, injustice and human rights denied.

Pope Pius XI, Divini illius Magistri (1929), 21

Literary and artistic works depict the struggles of societies, of families, and of individuals. They spring from the depths of the human heart, revealing its lights and its shadows, its hope and its despair. The Christian perspective goes beyond the merely human, and offers more penetrating criteria for understanding the human struggle and the mysteries of the human spirit. Furthermore, an adequate religious formation has been the starting point for the vocation of a number of Christian artists and art critics. In the upper grades, a teacher can bring students to: an even more profound appreciation of artistic works: as a reflection of the divine beauty in tangible form. Both the Fathers of the Church and the masters of Christian philosophy teach this in their writings on aesthetics—St. Augustine invites us to go beyond the intention of the artists in order to find the eternal order of God in the work of art; St. Thomas sees the presence of the Divine Word in art.

Congregation for Catholic Education, The Religious Dimension of Education in a Catholic School (1988) 61

The Catholic school should teach its pupils to discern in the voice of the universe the Creator Whom it reveals and, in the conquests of science, to know God and man better.

Congregation for Catholic Education, The Catholic School (1977) 46

…help their students to understand that positive science, and the technology allied to it, is a part of the universe created by God. Understanding this can help encourage an interest in research: the whole of creation, from the distant celestial bodies and the immeasurable cosmic forces down to the infinitesimal particles and waves of matter and energy, all bear the imprint of the Creator’s wisdom and power, The wonder that past ages felt when contemplating this universe, recorded by the Biblical authors, is still valid for the students of today; the only difference is that we have a knowledge that is much more vast and profound. There can be no conflict between faith and true scientific knowledge; both find their source in God. The student who is able to discover the harmony between faith and science will, in future professional life, be better able to put science and technology to the service of men and women, and to the service of God. It is a way of giving back to God what he has first given to us.

Congregation for Catholic Education, The Religious Dimension of Education in a Catholic School (1988) 54

Furthermore, when man gives himself to the various disciplines of philosophy, history and of mathematical and natural science, and when he cultivates the arts, he can do very much to elevate the human family to a more sublime understanding of truth, goodness, and beauty, and to the formation of considered opinions which have universal value. Thus mankind may be more clearly enlightened by that marvelous Wisdom which was with God from all eternity, composing all things with him, rejoicing in the earth and delighting in the sons of men. In this way, the human spirit, being less subjected to material things, can be more easily drawn to the worship and contemplation of the Creator. Moreover, by the impulse of grace, he is disposed to acknowledge the Word of God, Who before He became flesh in order to save all and to sum up all in Himself was already “in the world” as “the true light which enlightens every man” (John 1:9-10). Indeed today’s progress in science and technology can foster a certain exclusive emphasis on observable data, and agnosticism about everything else. For the methods of investigation which these sciences use can be wrongly considered as the supreme rule of seeking the whole truth. By virtue of their methods these sciences cannot penetrate to the intimate notion of things. Indeed the danger is present that man, confiding too much in the discoveries of today, may think that he is sufficient unto himself and no longer seek the higher things.

Saint Paul VI, Gaudium et Spes (1965) 57

Catholic schools strive to relate all of the sciences to salvation and sanctification. Students are shown how Jesus illumines all of life—science, mathematics, history, business, biology, and so forth.

U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, National Directory of Catechesis (2005) p.233

16. Integration of knowledge is a process, one which will always remain incomplete; moreover, the explosion of knowledge in recent decades, together with the rigid compartmentalization of knowledge within individual academic disciplines, makes the task increasingly difficult. But a University, and especially a Catholic University, “has to be a ‘living union’ of individual organisms dedicated to the search for truth … It is necessary to work towards a higher synthesis of knowledge, in which alone lies the possibility of satisfying that thirst for truth which is profoundly inscribed on the heart of the human person”(19). Aided by the specific contributions of philosophy and theology, university scholars will be engaged in a constant effort to determine the relative place and meaning of each of the various disciplines within the context of a vision of the human person and the world that is enlightened by the Gospel, and therefore by a faith in Christ, the Logos, as the centre of creation and of human history.

17. In promoting this integration of knowledge, a specific part of a Catholic University’s task is to promote dialogue between faith and reason,so that it can be seen more profoundly how faith and reason bear harmonious witness to the unity of all truth. While each academic discipline retains its own integrity and has its own methods, this dialogue demonstrates that “methodical research within every branch of learning, when carried out in a truly scientific manner and in accord with moral norms, can never truly conflict with faith. For the things of the earth and the concerns of faith derive from the same God”(20). A vital interaction of two distinct levels of coming to know the one truth leads to a greater love for truth itself, and contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the meaning of human life and of the purpose of God’s creation.

18. Because knowledge is meant to serve the human person, research in a Catholic University is always carried out with a concern for the ethical and moral implications both of its methods and of its discoveries. This concern, while it must be present in all research, is particularly important in the areas of science and technology. “It is essential that we be convinced of the priority of the ethical over the technical, of the primacy of the person over things, of the superiority of the spirit over matter. The cause of the human person will only be served if knowledge is joined to conscience. Men and women of science will truly aid humanity only if they preserve ‘the sense of the transcendence of the human person over the world and of God over the human person”(21).

23. Students are challenged to pursue an education that combines excellence in humanistic and cultural development with specialized professional training. Most especially, they are challenged to continue the search for truth and for meaning throughout their lives, since “the human spirit must be cultivated in such a way that there results a growth in its ability to wonder, to understand, to contemplate, to make personal judgments, and to develop a religious, moral, and social sense”(23). This enables them to acquire or, if they have already done so, to deepen a Christian way of life that is authentic. They should realize the responsibility of their professional life, the enthusiasm of being the trained ‘leaders’ of tomorrow, of being witnesses to Christ in whatever place they may exercise their profession.

28. Bishops have a particular responsibility to promote Catholic Universities, and especially to promote and assist in the preservation and strengthening of their Catholic identity, including the protection of their Catholic identity in relation to civil authorities. This will be achieved more effectively if close personal and pastoral relationships exist between University and Church authorities, characterized by mutual trust, close and consistent cooperation and continuing dialogue. Even when they do not enter directly into the internal governance of the University, Bishops “should be seen not as external agents but as participants in the life of the Catholic University”(27).

32. If need be, a Catholic University must have the courage to speak uncomfortable truths which do not please public opinion, but which are necessary to safeguard the authentic good of society.

33. A specific priority is the need to examine and evaluate the predominant values and norms of modern society and culture in a Christian perspective, and the responsibility to try to communicate to society those ethical and religious principles which give full meaning to human life. In this way a University can contribute further to the development of a true Christian anthropology, founded on the person of Christ, which will bring the dynamism of the creation and redemption to bear on reality and on the correct solution to the problems of life.

General Norms, Article 4

§ 4. Those university teachers and administrators who belong to other Churches, ecclesial communities, or religions, as well as those who profess no religious belief, and also all students, are to recognize and respect the distinctive Catholic identity of the University. In order not to endanger the Catholic identity of the University or Institute of Higher Studies, the number of non-Catholic teachers should not be allowed to constitute a majority within the Institution, which is and must remain Catholic.

§ 5. The education of students is to combine academic and professional development with formation in moral and religious principles and the social teachings of the Church; the programme of studies for each of the various professions is to include an appropriate ethical formation in that profession. Courses in Catholic doctrine are to be made available to all students.

St. John Paul II, Ex corde Ecclesiae (1990)

[1] For more on this topic see Pope Pius XI, Divini illius Magistri (1929).

[2] For more on this topic see Principles of Catholic Identity in Education by The Cardinal Newman Society at https://cardinalnewmansociety.org/principles-resources-catholic-education/.

[3] https://cardinalnewmansociety.org/educator-resources/resources/academics/catholic-curriculum-standards/

[4] https://cardinalnewmansociety.org/standards-christian-anthropology/

[5] Congregation for Catholic Education, The Catholic School (1977) 5-7; Saint Paul VI, Gravissimum Educationis (1965) 2; United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, To Teach as Jesus Did (1972) 7.

[6] Matthew 28:19-20.

[7] Holy See, Code of Canon Law (Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1983) 795; Congregation for Catholic Education (1965) Introduction; Congregation for Catholic Education, Circular Letter to the Presidents of Bishops’ Conferences on Religious Education in Schools (2009) 1.

[8] Congregation for Catholic Education, Educating Together in Catholic Schools: A Shared Mission Between Consecrated Persons and the Lay Faithful (2007) 5, 10; Congregation for Catholic Education, The Religious Dimension of Education in a Catholic School (1988) 44.

[9] Congregation for Catholic Education (2007) 5; Congregation for Catholic Education, Educating in Intercultural Dialogue in the Catholic School: Living in Harmony for a Civilization of Love (2013) 86; Congregation for Catholic Education, Lay Catholics in Schools: Witnesses to Faith (1982) 18; U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, Renewing Our Commitment to Catholic Elementary & Secondary Schools in the Third Millennium (2005).

[10] Congregation for Catholic Education (1977) 26; Congregation for Catholic Education (1972) 23, 108; Congregation for Catholic Education (2007) 12.

[11] Saint Paul VI (1965) 8; Code of Canon Law 803 §2; Congregation for Catholic Education (1972) 104.

[12] Code of Canon Law 795; Saint Paul VI (1965) Introduction; Congregation for Catholic Education (2009) 1.

[13] Congregation for Catholic Education (1982) 12.

[14] Catechism 355; Gen. 1:27.

[15] Catechism 362.

[16] Catechism 369.

[17] Catechism 402.

[18] Congregation for Catholic Education (1982) 12; Congregation for Catholic Education (1977) 26, 36; Congregation for Catholic Education (1988) 108.

[19] Congregation for Catholic Education (1977) 15, 49; Congregation for Catholic Education (1988) 34, 51, 52.

[20] Congregation for Catholic Education, The Catholic School on the Threshold of the Third Millennium (1997) 14; Congregation for Catholic Education (1988) 53, 100; Saint Paul VI (1965) 8.

[21] Congregation for Catholic Education (1988) 57.

[22] Saint John Paul II, Ad limina visit of bishops from Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin (May 30,1998); U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (2005); Congregation for Catholic Education, Educating Today and Tomorrow: A Renewing Passion (2014) II-1.